Next-generation nuclear reaches a turning point: Meta and major hyperscalers begin partnerships with Bill Gates’ TerraPower, Oklo supported by Sam Altman, and others

The Changing Face of Nuclear Innovation

Chris Levesque, who spent years working in both naval and commercial nuclear sectors, joined Bill Gates’ TerraPower about ten years ago. Despite his extensive background, he quickly realized that the concept of innovation was largely absent from the traditional nuclear industry.

For decades, nuclear power in the U.S. stagnated as natural gas and renewables took center stage, largely due to safety concerns and notorious cost overruns. The only significant expansion in nearly thirty years was Georgia’s Vogtle project, which ended up taking 15 years and costing over $35 billion—more than double its original estimates. This experience did little to encourage further nuclear investment.

“The U.S. has a strong safety record in nuclear, but that led to a culture where innovation was discouraged,” Levesque explained. “We were incentivized to repeat past processes with only minor improvements. Taking risks was frowned upon.”

When Levesque transitioned from Westinghouse to TerraPower, he encountered a company driven by curiosity: What can nature and science make possible?

A New Era for Nuclear Power

Nearly seventy years after America’s first nuclear plant began operation, the industry may be on the verge of a major revival. The emergence of small modular reactors (SMRs), soaring energy needs from AI data centers, and streamlined regulatory efforts under the Trump administration are converging. U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright has called this moment “the next American nuclear renaissance.”

In early 2025, Meta joined forces with TerraPower and Oklo, a company supported by Sam Altman, to develop around 4 gigawatts of SMR projects—enough to supply nearly 3 million homes. These projects aim to provide clean, dependable power for Meta’s upcoming Prometheus AI campus in Ohio and other sites.

Industry experts believe Meta’s move is just the beginning, predicting that other tech giants will soon follow with their own nuclear initiatives, whether through partnerships or acquisitions.

Dan Ives, head of tech research at Wedbush Securities, remarked, “Meta’s deal is just the start. I’d be surprised if every major tech company doesn’t pursue nuclear energy in some form by 2026.”

Ives also noted the unprecedented pace of data center construction in the U.S., stating, “Nuclear energy is likely the solution for clean, reliable power. By 2030, we could see nuclear reach a scale that launches a new era for the industry.”

SMRs: Fast, Flexible, and Scalable

Unlike traditional reactors, which can take a decade to build, SMRs can be constructed in as little as three years. Their modular nature allows for incremental expansion to meet the growing energy needs of hyperscalers—the companies behind massive data centers.

Jacob DeWitte, CEO of Oklo, emphasized the urgency: “If nuclear doesn’t advance, we face significant risks. We need emission-free, reliable power to keep up with demand.”

DeWitte added, “Hyperscalers recognize the real market opportunity and can play a pivotal role in making new nuclear projects a reality. We’re finally seeing genuine innovation in the sector for the first time since nuclear power’s inception.”

Revitalizing Nuclear Growth

The rise of shale drilling made natural gas the dominant force in U.S. electricity generation, now accounting for over 40% of the grid. However, with gas prices climbing and turbine orders delayed, hyperscalers are seeking alternative, cleaner energy sources for the long term.

Wind and solar, which together provide over 15% of U.S. electricity, have been attractive options. Yet, the expiration of federal subsidies and the impact of tariffs are driving up costs.

As a result, nuclear—currently under 20% of the grid—is regaining attention, thanks to technological advances, bipartisan support, and regulatory reforms. With U.S. electricity demand projected to increase by 50% to 80% by 2050, expanding energy sources is crucial.

Levesque noted, “The electricity sector moves much slower than tech, but now the two are colliding as AI drives up demand. Our SMRs are designed to compete with gas-fired plants on cost.”

TerraPower is building its first 345-megawatt SMR plant in Wyoming, aiming to complete it by 2030 and connect it to the grid in 2031.

The company’s agreement with Meta includes two reactors scheduled to be operational by 2032, with the potential for six more, totaling up to 2.8 gigawatts.

“This Meta deal is shaping our project pipeline,” Levesque said. “We’re in talks with other partners and expect to have about a dozen plants under construction when the Wyoming facility launches, several of which could be for Meta.”

Partnering with Tech Giants

Oklo, founded in 2013 by Jacob and Caroline DeWitte, plans to begin building its first reactors in Pike County, Ohio, near Meta’s future Prometheus data center. The initial units could be online by 2030, with the site scaling up to 1.2 gigawatts by 2034.

Meanwhile, Oklo is constructing its Aurora Powerhouse test reactor at Idaho National Laboratory as part of a federal pilot program. Oklo leads with three of the eleven projects in development; no other company has more than one. Aurora is expected to be operational by 2027 or 2028.

“Idaho is our starting point, but Ohio will be a major focus,” DeWitte said. “We’re committed to expanding our presence and building more facilities there.”

The DeWittes, who met at MIT’s nuclear engineering department, have deep roots in the industry. They connected with Sam Altman in Oklo’s founding year, forming a close partnership based on a shared belief in the need for clean, advanced nuclear power.

Altman became an early investor and served as Oklo’s chairman until 2025. Though he stepped down to avoid conflicts with hyperscalers competing with OpenAI, he retains a significant ownership stake.

“Hyperscalers are ideal partners for accelerating new power generation,” DeWitte explained. “Their willingness to move quickly and invest resources helps reduce project risks and brings new capacity online faster, which in turn lowers costs and enables more plant construction.”

Oklo’s market value now exceeds $11 billion, having grown nearly 50% in the past year despite volatility.

Inside the Technology

Traditional nuclear plants rely on light-water reactors, which use regular water for both pressure and cooling.

TerraPower and Oklo, however, are developing sodium-cooled reactors. Sodium offers superior heat transfer and allows for low-pressure systems, reducing the need for heavy containment structures made of concrete and steel.

Levesque explained that TerraPower’s natrium system requires less than half the steel, concrete, and labor per megawatt compared to conventional designs.

“We’re still using fission—splitting uranium atoms to generate heat and drive turbines,” Levesque said. “But by switching to liquid sodium for cooling, we can build lighter, more efficient plants.”

The sodium design also uses air-cooled chimneys for passive safety during shutdowns, eliminating the need for external emergency power and water systems.

While countries like Russia, China, and India have pursued sodium-cooled reactors for years, the U.S. is now catching up. These modern designs are inspired by the Argonne National Lab’s EBR-II reactor, which demonstrated the viability of sodium-cooled fast reactors decades ago.

“Frankly, the industry became accustomed to high costs because it could,” DeWitte commented.

TerraPower has also integrated molten-salt energy storage, functioning as a “thermal battery” to store excess energy for use during peak demand, potentially replacing the need for gas-fired peaker plants.

With two reactors, TerraPower can provide 690 megawatts of steady power, but the storage system allows up to 1 gigawatt of electricity to be dispatched during periods of high demand or outages.

Beyond construction and labor, a major cost factor is enriched uranium, with Russia controlling nearly half the global enrichment market. The U.S. is working to strengthen its own uranium supply chain, while Oklo is investing in nuclear fuel recycling to reduce reliance on new material. Since only about 5% of uranium’s energy is used in a reactor, recycling spent fuel could significantly extend resources.

Oklo is building a $1.7 billion recycling facility in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, aiming to launch by 2030, though the technology is still being refined.

In the interim, Oklo may use plutonium as a transitional fuel and has partnered with Liberty Energy to provide temporary gas-fired power for data centers until its SMRs are ready.

“Recycling is a game changer,” DeWitte said. “With recycling, America’s uranium reserves could power the nation for over 150 years.”

Regulatory Challenges and Industry Concerns

The nuclear industry’s resurgence is not without controversy.

The White House aims to quadruple U.S. nuclear capacity from 100 to 400 gigawatts by 2050—enough to power nearly 300 million homes, far more than the current number of households.

To achieve this, the Trump administration is combining a new reactor program with a major overhaul of nuclear safety regulations, shifting more oversight to the Department of Energy from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

The DOE claims it is streamlining regulations without compromising safety. However, groups like the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) worry that safety is being sacrificed in the rush to support the global AI race.

Edwin Lyman, UCS director of nuclear power safety, criticized the changes: “The Energy Department has undermined the core principles of effective nuclear regulation, often without public transparency. These principles were developed from hard lessons like Chernobyl and Fukushima.”

Despite these concerns, startups such as Oklo, Antares Nuclear, and Natura Resources are moving forward, arguing that their smaller, safer reactors are fundamentally different from those involved in past disasters.

Recently, Antares received preliminary safety approval for its Mark-0 demonstration reactor in Idaho, set to launch this summer.

In February, Natura announced plans for a 100-megawatt reactor to power oil, gas, and water treatment facilities in Texas’ Permian Basin, along with another DOE-backed project at Abilene Christian University.

Elsewhere, Kairos Power is building a demonstration reactor in Tennessee and has a deal to supply 500 megawatts of SMR power to Google by 2035. Amazon is supporting x-Energy’s plan to build 5 gigawatts of SMR capacity by 2039, including 1 gigawatt in Washington state.

The nuclear revival isn’t limited to SMRs. With federal backing, Westinghouse is constructing ten pre-licensed AP1000 reactors—the same model as Vogtle—by 2030, each with a capacity of 1.1 gigawatts.

DeWitte sees value in both large and small reactors: “It’s not about choosing between big and small. Large reactors are vital in some contexts but require significant capital. Smaller reactors are easier to finance and build quickly, allowing for faster innovation and cost reductions.”

This article was originally published on Fortune.com.

Disclaimer: The content of this article solely reflects the author's opinion and does not represent the platform in any capacity. This article is not intended to serve as a reference for making investment decisions.

You may also like

Polygon price double bottoms as Tazapay, Revolut, Paxos, and Moonpay payments rise

Trump disclaims UAE World Liberty stake knowledge, Gemini exits, China bans yuan stablecoins | Weekly Recap

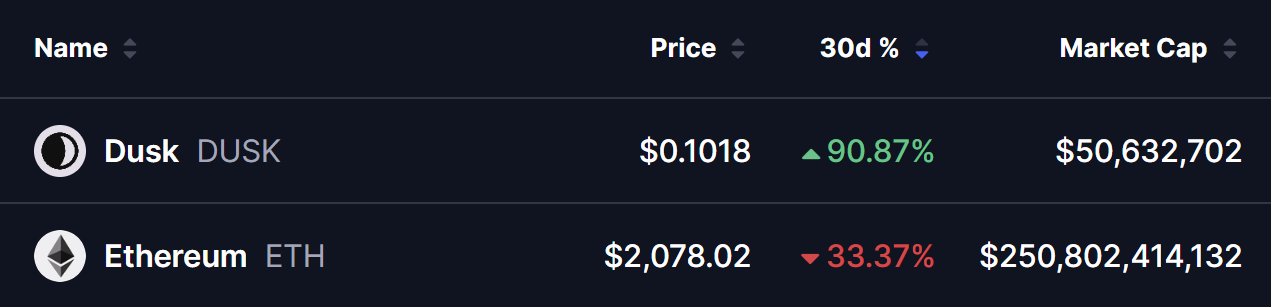

Dusk (DUSK) Testing Key Resistance — Is an Upside Breakout on Horizon?

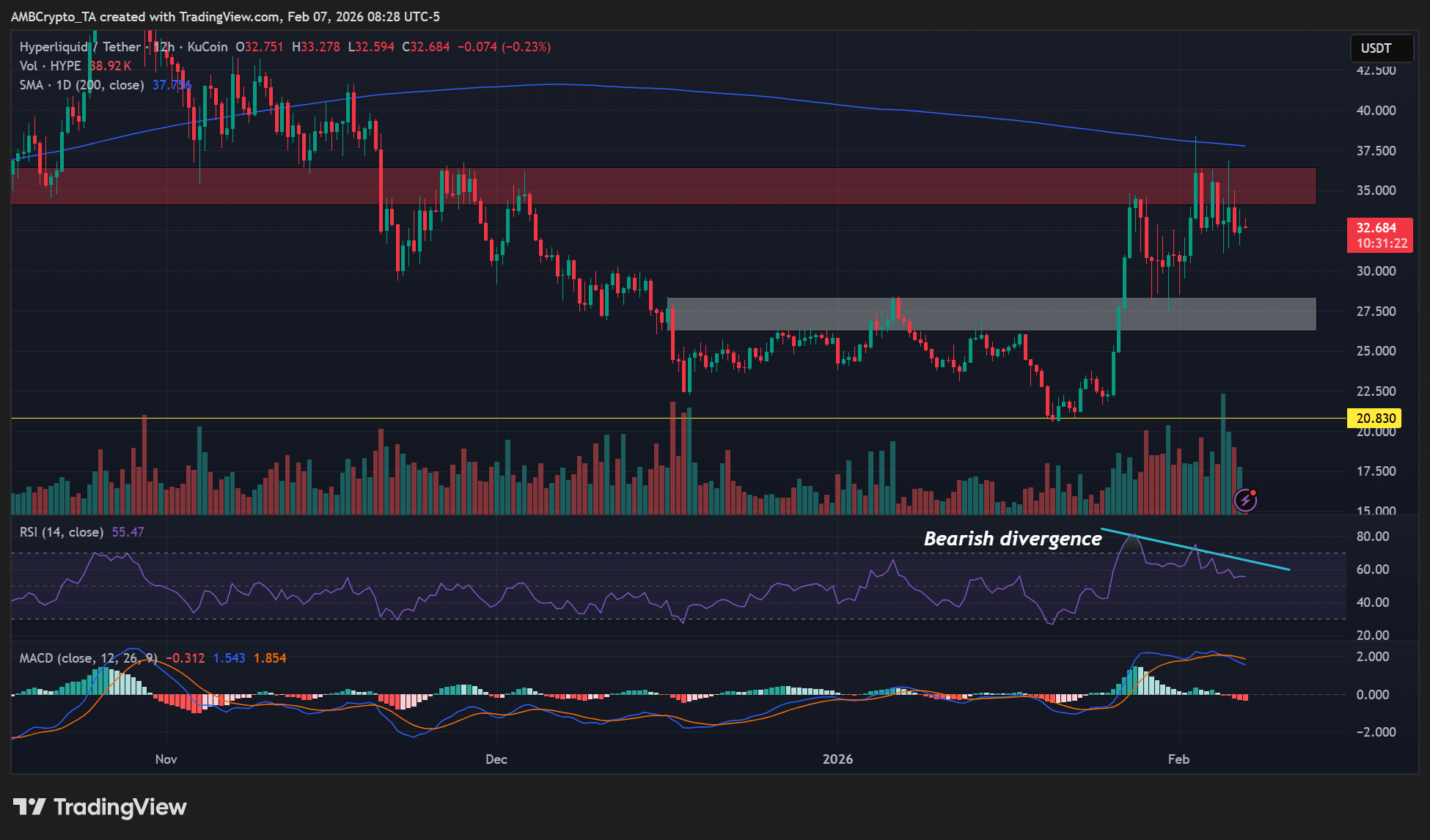

Hyperliquid – Record daily revenue of $6.84M, but HYPE hits the brakes