Markets don’t reach their lowest point because of fear; they hit bottom once all compelled sellers have exited.

Understanding Recent Market Downturns

Markets have experienced a sharp decline, with sentiment turning more cautious. Volatility is on the rise, bearish voices are becoming more prominent, and cash is once again in favor. Downward moves are outweighing gains, and assets are moving in closer tandem. What does this shift mean for investors?

Many misunderstand what drives these market moves. Markets don't reach their lowest point simply because investors are anxious. Instead, bottoms form when the wave of forced selling subsides. While fear is psychological, forced selling is a result of structural pressures, and prices react to these underlying forces.

Featured Insights from Barchart

Current Trading Landscape

At present, the focus isn't on predicting a broad economic turning point. Instead, the opportunity lies in spotting where liquidity-driven selling has pushed prices far from the underlying fundamentals of businesses.

We are in a period where risk is being systematically reduced. Funds that began the year fully invested are now managing losses, risk controls are tightening, and margin requirements are stricter. Passive investment flows can intensify redemptions, and as volatility increases, quantitative strategies cut back on exposure. This process doesn't require a collapse in earnings—just a shift in positioning. That's why markets can drop sharply even when forward earnings estimates remain steady. The key question isn't whether we've hit the bottom, but rather, "Who is being forced to sell, and when will that pressure end?"

There are specific periods when the supply of shares for sale dries up.

Upcoming Catalysts and Market Dynamics

The next month or so will be filled with earnings announcements. These events are important not because results will be flawless, but because they create moments of liquidity. Companies reaffirm guidance, update on backlogs, discuss refinancing, and reset expectations. Weaker holders may use these events to exit, while more confident investors step in as uncertainty fades.

Beyond earnings, it's important to examine companies' debt schedules. Debt coming due within the next year can distinguish between businesses facing structural challenges and those simply experiencing share price swings. Firms with staggered maturities, ample covenant room, and strong cash flow aren't necessarily in trouble just because their stock has dropped.

Refinancing opportunities in the coming quarters could serve as a catalyst. If companies can extend debt at reasonable rates, equity risk can quickly diminish. If not, the investment thesis may need to change. In special situations, these catalyst windows are even more defined—spinoffs have set dates, breakups require board approval and filings, and lockup expirations release shares on a known schedule. These events often trigger mandated selling by index funds, income funds, or generalists who don't want exposure to the new entity. This is structural, not emotional, selling.

Lessons from Past Market Cycles

History shows this pattern repeatedly. In 2008, 2011, and 2020, prices stabilized before investor sentiment improved. Liquidity steadied first, and only then did headlines turn positive. When a company's incentives align and temporary selling pressure sets the price, structural opportunities arise. For example, after a spinoff, a business that was previously part of a larger conglomerate can focus on its own performance, leading to better capital discipline and more rational decisions.

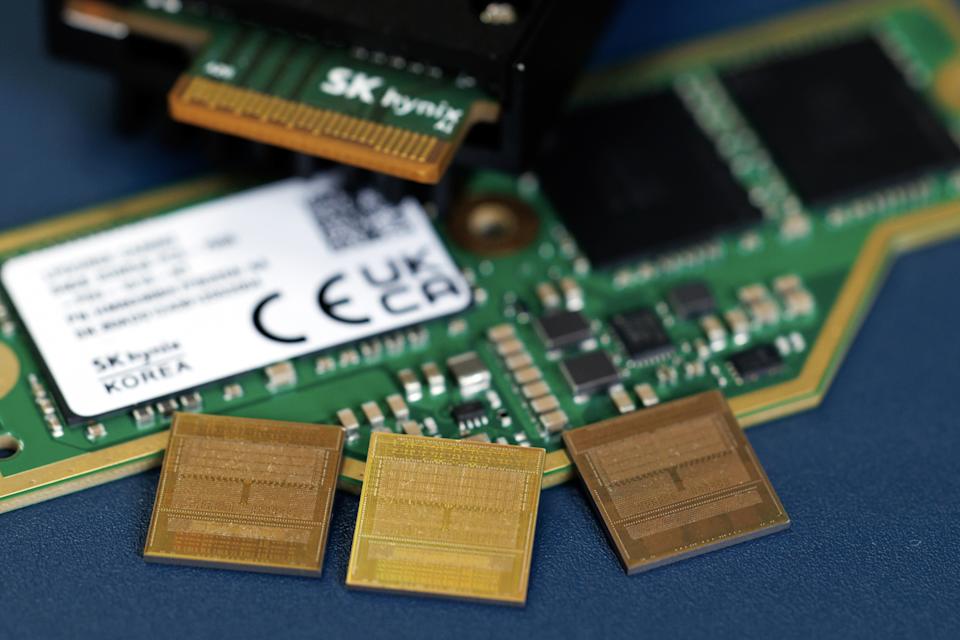

A recent case is SanDisk (SNDK) after its separation from Western Digital (WDC) in April 2024. The stock dropped sharply post-breakup, not due to falling demand or a balance sheet crisis, but because of mechanical selling. Index funds adjusted, and generalist investors who owned WDC for its diversified exposure were not natural holders of a standalone memory business. Once this structural selling ended, SanDisk became one of the top-performing S&P stocks over the following year.

By mid-April, trading volume decreased even as news coverage remained cautious. Prices stopped hitting new lows before the broader semiconductor sector recovered. The forced selling had ended, and the business fundamentals hadn't changed—only the liquidity had. This is how market bottoms are formed. During these periods, prices often fall not because the business has worsened, but because previous holders sell the new, smaller entity. Funds with minimum size requirements must exit, regardless of the company's intrinsic value. This is the process of forming a bottom.

The same pattern appears after dividend cuts. Income-focused funds sell automatically, algorithms react, and prices drop. Yet, if the dividend cut strengthens the balance sheet and extends debt maturities, long-term value can improve even as the price falls.

How to Track Market Bottoms

To connect fundamentals with price action, monitor trading volume and relative strength. Heavy volume during declines is typical in forced selling. What matters is what happens next—if subsequent lows are tested on lighter volume, it suggests selling pressure is easing. If a stock stops underperforming its sector during market weakness, that's a positive sign. Relative strength often improves before the price itself does. Short interest is also important; rising short interest during market stress may reflect hedging, not conviction. If short positions increase while prices stabilize, the setup is changing and potential for a rebound grows.

Options activity can also provide clues. When demand for put options surges, it signals peak fear, though this alone isn't a buy signal. The bottom is often reached when demand for protection fades as forced sellers exit.

It's crucial to define risk clearly. If earnings reveal a real drop in demand, not just temporary margin pressure, the outlook changes. If refinancing fails or borrowing costs rise sharply, leverage becomes a bigger concern. If planned separations are delayed or boards back away from strategic moves, the structural opportunity disappears.

Macro-level liquidity is another factor. External shocks can prolong forced selling beyond what fundamentals justify. That's why it's wise to build positions gradually, accumulating as selling pressure wanes rather than trying to catch a falling knife.

The setup is invalidated if prices keep falling on increasing volume after catalysts have passed and no new negative news emerges. If earnings are steady, debt is refinanced, and separations proceed as planned, yet prices continue to drop, something else is at play. The market doesn't reward bravery or punish fear—it simply responds to money flows. Right now, those flows are negative, but they are not endless. For active traders, the approach should be tactical: focus on financially sound companies with clear upcoming catalysts, watch for signs of selling exhaustion, and compare relative strength to peers. If earnings confirm stable cash flow and prices hold support on lighter volume, it signals the end of forced selling.

Strategies for Different Investors

- Income investors: Prioritize companies with strong coverage ratios and well-spaced debt maturities. If free cash flow covers dividends and debt is not coming due soon, price swings don't necessarily mean insolvency.

- Catalyst-driven investors: Focus on key dates—earnings calls, board meetings, separation filings, refinancing announcements. If these events pass without structural setbacks and prices stop making new lows, selling pressure has likely eased.

Markets don't announce when they've bottomed—there's no signal when the last seller exits. The price simply stops reacting to negative news and begins to absorb it. That's the turning point that matters.

Fear is noisy, but forced selling is mechanical. Once that pressure lifts, prices tend to move back toward business fundamentals. We're entering a period filled with catalysts: earnings, refinancing updates, and strategic actions across sectors. This is when liquidity resets. If earnings confirm resilience and technical levels hold on lighter volume, selectively adding to strong balance sheet situations is reasonable. If refinancing is successful and leverage concerns fade, equities can reprice quickly. If separations proceed and management incentives align with shareholders, value can be unlocked even as sentiment remains cautious.

The real opportunity isn't in guessing the next headline, but in recognizing when forced sellers have finished. Markets find their bottom when supply dries up—not when fear is at its peak.

When the selling ends, the price will show it.

Disclaimer: The content of this article solely reflects the author's opinion and does not represent the platform in any capacity. This article is not intended to serve as a reference for making investment decisions.

You may also like

Rampant AI-driven demand for memory is intensifying the ongoing chip shortage

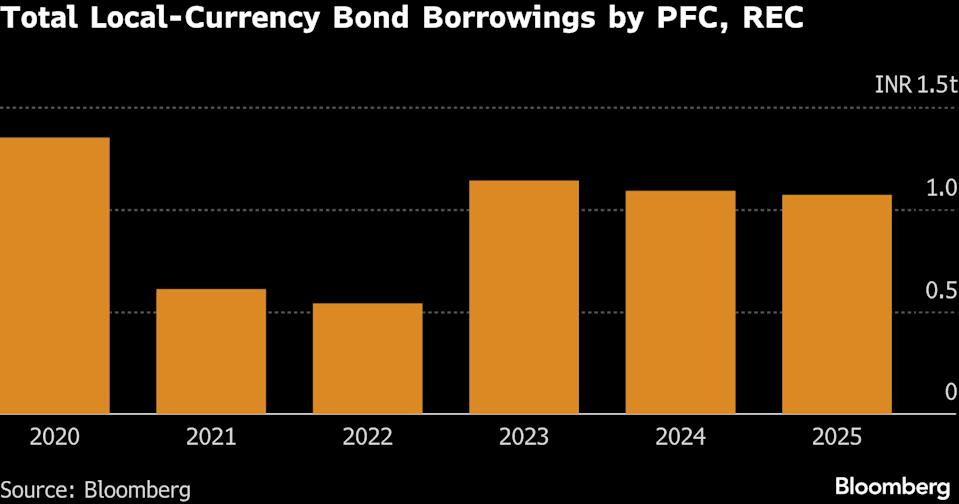

Merger With $61 Billion Debt Set to Boost India's Credit Market

Quantra Shakes Hands with Chain Intelligence for Amplifying Web3 Infrastructure